Tuskegee University

| |

| Motto | Scientia Principatus Opera |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Knowledge, Leadership, Service |

| Type | Private, HBCU, Land-grant |

| Established | July 4, 1881 (1881-07-04) |

| Founder | Booker T. Washington |

Academic affiliations | UNCF NAICU[1] APLU ORAU |

| Endowment | $130.2 million (2014) |

| President | Lily McNair |

| Students | 3,140 (2017)[2] |

| Location | Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S. 32°25′48.76″N 85°42′27.81″W / 32.4302111°N 85.7077250°W / 32.4302111; -85.7077250 |

| Campus | Rural, 5,200 acres |

| Colors | Crimson and Gold[3] |

| Nickname | Golden Tigers |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division II – SIAC |

| Website | www.tuskegee.edu |

| |

Tuskegee University is a private, historically black university (HBCU) located in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It was established by Lewis Adams and Booker T. Washington. The campus is designated as the Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site by the National Park Service and is the only one in the U.S. to have this designation. The university was home to scientist George Washington Carver and to World War II's Tuskegee Airmen.

Tuskegee University offers 40 bachelor's degree programs, 17 master's degree programs, a 5-year accredited professional degree program in architecture, 4 doctoral degree programs, and the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine. The university is home to over 3,100 students from the U.S. and 30 foreign countries. Tuskegee University was ranked among 2018's best 379 colleges and universities by The Princeton Review and 6th among the 2018 U.S. News & World Report best HBCUs.

The university's campus was designed by architect Robert Robinson Taylor, the first African American to graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Planning and establishment

1.2 Booker T. Washington's leadership

1.3 1881–1900

1.4 1900–1915

1.5 1915–1940

1.6 Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

1.7 World War II and after

1.8 Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site

1.9 Legacy

2 Tuskegee University campus

3 The Tuskegee University Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center

4 Academics

4.1 Rankings

4.2 Schools and colleges

4.3 National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care

5 Athletics

5.1 Football

5.2 Baseball

5.3 Softball

5.4 Basketball

5.5 Track and field

6 Student organizations

7 Notable faculty and staff

8 Notable alumni

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

History

Planning and establishment

History class at Tuskegee, 1902

The school was founded on July 4, 1881, as the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers. This was a result of an agreement made during the 1880 elections in Macon County between a former Confederate Colonel, W.F. Foster, who was running on the democratic ticket and a local Black Leader and Republican, Lewis Adams. W.F. Foster propositioned that if Adams could successfully persuade the Black constituents to vote for Foster, if elected, Foster would push the state of Alabama to establish a school for Black people in the county. At the time the majority of Macon County population was Black, thus Black constituents had political power. Adams succeeded and Foster followed through with the school.[citation needed] The school became a part of the expansion of higher education for blacks in the former Confederate states following the American Civil War, with many schools founded by the northern American Missionary Association. A teachers' school was the dream of Lewis Adams, a former slave, and George W. Campbell, a banker, merchant, and former slaveholder, who shared a commitment to the education of blacks. Despite lacking formal education, Adams could read, write, and speak several languages. He was an experienced tinsmith, harness-maker, and shoemaker and was a Prince Hall Freemason, an acknowledged leader of the African-American community in Macon County, Alabama.

Adams and Campbell had secured $2,000 from the State of Alabama for teachers' salaries but nothing for land, buildings, or equipment. Adams, Campbell (replacing Thomas Dryer, who died after his appointment), and M. B. Swanson formed Tuskegee's first board of commissioners. Campbell wrote to the Hampton Institute, a historically black college in Virginia, requesting the recommendation of a teacher for their new school. Samuel C. Armstrong, the Hampton principal and a former Union general, recommended 25-year-old Booker T. Washington, an alumnus and teacher at Hampton. The Tuskegee Railroad was 5 and 1/2 miles from Tuskegee to Selma. It was destroyed in the Civil War but then rebuilt in 1880 to connect the Tuskegee Institute to other railroad lines.

As the newly hired principal in Tuskegee, Booker Washington began classes for his new school in a rundown church and shanty. The following year (1882), he purchased a former plantation of 100 acres in size. In 1973 Tuskegee Institute now Tuskegee University did an oral history interview with Annie Lou "Bama" Miller. In that interview she indicated that her grand mother sold the original 100 acres of land to Booker T. Washington. That oral history interview is located at the Tuskegee University archives. The earliest campus buildings were constructed on that property, usually by students as part of their work-study. By the start of the 20th century, the Tuskegee Institute occupied nearly 2,300 acres.[4]

Based on his experience at the Hampton Institute, Washington intended to train students in skills, morals, and religious life, in addition to academic subjects. Washington urged the teachers he trained "to return to the plantation districts and show the people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as into the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people."[5] Washington's second wife Olivia A. Davidson, was instrumental to the success and helped raise funds for the school.[6]

Gradually, a rural extension program was developed, to take progressive ideas and training to those who could not come to the campus. Tuskegee alumni founded smaller schools and colleges throughout the South; they continued to emphasize teacher training.

Booker T. Washington's leadership

Booker T. Washington

The Oaks, Booker T. Washington's home on the Tuskegee campus, c. 1906

Booker T. Washington | 1881–1915 |

Robert Russa Moton | 1915–1935 |

Frederick Douglass Patterson | 1935–1953 |

Luther H. Foster Jr. | 1953–1981 |

Benjamin F. Payton | 1981–2010 |

Charlotte P. Morris (interim) | 2010–2010 |

Gilbert L. Rochon | 2010–2013 |

Matthew Jenkins (acting) | 2013–2014 |

Brian L. Johnson | 2014–2017 |

Charlotte P. Morris (interim) | 2017–2018 |

Lily D. McNair | 2018–present |

As a young free man after the Civil War, Washington sought a formal education. He worked his way through Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) and attended college at Wayland Seminary in Washington, DC (now Virginia Union University). He returned to Hampton as a teacher.

Hired as principal of the new normal school (for the training of teachers) in Tuskegee, Alabama, Booker Washington opened his school on July 4, 1881, on the grounds of the Butler Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. The following year, he bought the grounds of a former plantation. Over the decades he expanded the institute there; It has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.

The school expressed Washington's dedication to the pursuit of self-reliance. In addition to training teachers, he also taught the practical skills needed for his students to succeed at farming or other trades typical of the rural South, where most of them came from. He wanted his students to see labor as practical, but also as beautiful and dignified. As part of their work-study programs, students constructed most of the new buildings. Many students earned all or part of their expenses through the construction, agricultural, and domestic work associated with the campus, as they reared livestock and raised crops, as well as producing other goods.

The continuing expansion of black education took place against a background of increased violence against blacks in the South, after white Democrats regained power in state governments and imposed white supremacy in society. They instituted legal racial segregation and a variety of Jim Crow laws, after disfranchising most blacks by constitutional amendments and electoral rules from 1890 until 1964. Against this background, Washington's vision, as expressed in his "Atlanta compromise" speech, became controversial and was challenged by new leaders, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, who argued that blacks should have opportunities for study in classical academic programs, as well as vocational institutes. In the early twentieth century, Du Bois envisioned the rise of "the Talented Tenth" to lead African Americans.

Washington gradually attracted notable scholars to Tuskegee, including the botanist George Washington Carver, one of the university's most renowned professors.

1881–1900

Perceived as a spokesman for black "industrial" education, Washington developed a network of wealthy American philanthropists who donated to the school, such as Andrew Carnegie, Collis P. Huntington, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Huttleston Rogers, George Eastman, and Elizabeth Milbank Anderson. An early champion of the concept of matching funds, Henry H. Rogers was a major anonymous contributor to Tuskegee and dozens of other black schools for more than fifteen years.

Thanks to recruitment efforts on the island and contacts with the U.S. military, Tuskegee had a particularly large population of Afro-Cuban students during these years. Following small-scale recruitments prior to the 1898–99 school year, the university quickly gained popularity among ambitious Afro-Cubans. In the first three decades of the school's existence, dozens of Afro-Cubans enrolled at Tuskegee each year, becoming the largest population of foreign students at the school.[7]

1900–1915

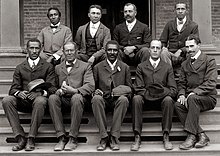

George Washington Carver (front row, center) poses with fellow faculty of Tuskegee Institute in this c. 1902 photograph taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston.

Washington developed a major relationship with Julius Rosenwald, a self-made man who rose to the top of Sears, Roebuck and Company in Chicago, Illinois. He had long been concerned about the lack of educational resources for blacks, especially in the South. After meeting with Washington, Rosenwald agreed to serve on Tuskegee's Board of Directors. He also worked with Washington to stimulate funding to train teachers' schools such as Tuskegee and Hampton institutes.

Washington was a tireless fundraiser for the institute. In 1905 he kicked off an endowment campaign, raising money all over America in 1906 for the 25th anniversary of the institution. Along with wealthy donors, he gave a lecture at Carnegie Hall in New York on January 23, 1906, called the Tuskegee Institute Silver Anniversary Lecture, in which Mark Twain spoke.

Beginning with a pilot program in 1912, Rosenwald created model rural schools and stimulated construction of new schools across the South. Tuskegee architects developed the model plans, and some students helped build the schools. Rosenwald created a fund but required communities to raise matching funds, to encourage local collaboration between blacks and whites. Rosenwald and Washington stimulated the construction and operation of more than 5,000 small community schools and supporting resources for the education of blacks throughout the rural the South into the 1930s.

Despite his travels and widespread work, Washington continued as principal of Tuskegee. Concerned about the educator's health, Rosenwald encouraged him to slow his pace. In 1915, Washington died at the age of 59, as a result of high blood pressure.[8] At his death, Tuskegee's endowment exceeded US$1.5 million. He was buried on the campus near the chapel.

Tuskegee, in cooperation with church missionary activity, work to set up industrial training programs in Africa.[9]

1915–1940

Tuskegee Institute, c. 1916

The years after World War I challenged the basis of the Tuskegee Institute. Teaching was still seen as a critical calling, but southern society was changing rapidly. Attracted by the growth of industrial jobs in the North, including the rapid expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad, suffering job losses because of the boll weevil and increasing mechanization of agriculture, and fleeing extra-legal violence, hundreds of thousands of rural blacks moved from the South to Northern and Midwestern industrial cities in the Great Migration. A total of 1.5 million moved during this period. In the South, industrialization was occurring in cities such as Birmingham, Alabama and other booming areas. The programs at Tuskegee, based on an agricultural economy, had to change. During and after World War II, migration to the North continued, with California added as a destination because of its defense industries. A total of 5 million blacks moved out of the South from 1940–1970.

Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

From 1932 to 1972, Tuskegee Institute collaborated with the United States government in the Tuskegee syphilis experiment by which the effects of deliberately untreated syphilis were studied. These experiments have become infamous for misleading study participants by telling them that they were being treated for syphilis when in fact researchers were only monitoring the progression of the disease. Syphilis is a debilitating disease that can leave its victims with permanent neurological damage and horrifying scars (see granulomatous gummas). Penicillin was discovered in 1927 and it was being used to treat human disease by the early 1940s. In 1947 it had become the gold standard in treating syphilis and often only required one intramuscular dose to completely eliminate the disease. The researchers were well aware of this information and in order to continue their experiments, they chose to withhold the life-saving treatment. The researchers proceeded to actively deter study participants from obtaining penicillin from other physicians. The patients were told that they had "bad blood." This experiment was conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service in collaboration with the Tuskegee Institute. This was a direct violation of the Hippocratic Oath, however, not a single researcher, nor the Tuskegee University was legally punished.

World War II and after

Tuskegee University Chapel (1969)

In 1941, in an effort to train black aviators, the U.S. Army Air Corps established a training program at Tuskegee Institute, using Moton Field, about 4 miles (6.4 km) away from the campus center. The graduates became known as the Tuskegee Airmen. The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site at Moton Field was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998. Army, Air Force, and Navy have R.O.T.C. programs on campus today.

Numerous presidents have visited Tuskegee, including Franklin D. Roosevelt. Eleanor Roosevelt was also interested in the Institute and its aeronautical school. In 1941 she visited Tuskegee Army Air Field and worked to have African Americans get the chance as pilots in the military. She corresponded with F.D. Patterson, the third president of the Tuskegee Institute, and frequently lent her support to programs.[10]

The notable architect Paul Rudolph was commissioned in 1958 to produce a new campus master plan. In 1960 he was awarded, along with the partnership of John A. Welch and Louis Fry, the commission for a new chapel, perhaps the most significant modern building constructed in Alabama.

The postwar decades were a time of continued expansion for Tuskegee, which added new programs and departments, adding graduate programs in several fields to reflect the rise of professional studies. For example, its School of Veterinary Medicine was added in 1944. Mechanical Engineering was added in 1953, and a four-year program in Architecture in 1957, with a six-year program in 1965.

In 1985, Tuskegee Institute achieved university status and was renamed Tuskegee University.

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

Show map of Alabama  Show map of the US | |

| Nearest city | Tuskegee, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°25′49″N 85°42′28″W / 32.43028°N 85.70778°W / 32.43028; -85.70778Coordinates: 32°25′49″N 85°42′28″W / 32.43028°N 85.70778°W / 32.43028; -85.70778 |

| Built | 1882 |

| Architect | Robert Robinson Taylor |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Queen Anne |

| Website | Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site |

| NRHP reference # | 66000151 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[11] |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1965[12] |

In 1965 Tuskegee University was declared a National Historic Landmark for the significance of its academic programs, its role in higher education for African-Americans, and its status in United States history.[12] Congress authorized the establishment of the Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site.

The National Historic Site includes The Oaks, Booker T. Washington's home and the George Washington Carver Museum. As the landmark designation did not define a limited area, the district is believed to have included the entire Tuskegee University campus at the time.[13]

Points of "special historic interest," noted in the landmark description include:[13]

- The Oaks (Washington's Home)

- Booker T. Washington monument, Lifting the Veil of Ignorance statue by Charles Keck

- Grave of Booker T. Washington

- Grave of George Washington Carver

- The George Washington Carver Museum

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site is at Moton Field, in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Legacy

Built in 1857, Grey Columns now serves as the home of the president of Tuskegee University. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 11, 1980.

The Tuskegee Institute commissioned a documentary[when?] about the college for use as a marketing tool and to preserve memories of Washington. A Tuskegee Pilgrimage, was a collection of interviews with faculty and students. It was produced by Robert Levy, who in 1922 had made an independent documentary about Washington, titled The Leader of His Race.

Tuskegee University campus

Tuskegee University provides 24-hour Campus Police protection for its students. All officers are state certified.

The Lifting the Veil of Ignorance statue of Booker T. Washington was designed by sculptor Charles Keck and unveiled on April 5, 1922. The statue depicts Dr. Washington lifting the veil of ignorance off his people, who had once been enslaved, by showing them the ways of a better life through education and skills.

James Henry Meriwether Henderson Hall is Tuskegee University's new Agricultural Life Science Teaching, Extension and Research Building. Henderson Hall provides labs for teaching introductory courses in animal, plant, soil, and environmental sciences as well as biology and chemistry.

Built in 1906 and completely renovated in 2013, Tompkins Hall serves as the primary student dining facility and student center. The building includes a ballroom, an auditorium, a game room, a retail restaurant, and a 24-hour student study with healthy food vending machines. It is home to the offices of the Student Government Association.

The Legacy Museum houses: The African collection (contains approximately 900 items), the antiques and miscellaneous items collection and The Lovette W. Harper Collection of African Art. Third Floor exhibition contains "The United States Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study in the Negro Male, Macon County, Alabama 1932-1972."

Booker T. Washington is laid to rest in the Tuskegee University Campus Cemetery. Many other notable university people are interred on the Tuskegee campus including: George Washington Carver, Cleveland L. Abbott, William L. Dawson, Luther Hilton Foster (4th president), Frederick D. Patterson (3rd president), many other Washington family members and others.

Tuskegee University provides on-campus apartment style living for students in the Commons Apartments located across the campus in three different locations

Margaret Murray Washington Hall is home to Office of Admission, University Bookstore and additional dining services for the students

"The Avenue" is one of the main pedestrian corridors on campus that is rarely open to vehicular traffic

Booker T. Washington Boulevard is the main drive into the campus of Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University's campus has a park like setting and features many large green areas

College of Veterinary Medicine Williams Bowie Hall

Tuskegee football game

Main entrance to the campus

A scenic campus corridor

Interior view of the Tuskegee Chapel

Fall at Tuskegee University

George Washington Carver Museum

The Main Library, Hollis Burke Frissell now known as the Ford Motor Company Library/Learning Resource Center

Campus banners

Andrew F. Brimmer College of Business and Information Sciences

Daniel "Chappie" James Center

Daniel "Chappie" James Center -Tuskegee basketball pre-game warm-up

Daniel "Chappie" James Center basketball game

Tuskegee University campus partial view of the "Valley" and the Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center

I-85 exit for Tuskegee University

The Tuskegee University Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center

The Tuskegee University Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center

The Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center at the renovated Dorothy Hall (built 1901) was established in 1994 on the campus of Tuskegee University by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The Kellogg Conference Center offers state-of-the-art multimedia meeting rooms, as well as a 300-seat auditorium and a ballroom that accommodates up to 350 guests. Students studying Hospitality Management within the Andrew F. Brimmer College of Business and Information Science & Dietetics students within the Department of Food and Nutrition Science are able to receive hands on experience at the Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center. The Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center is the only center at a historically black university; there are only 11 worldwide. Other Kellogg Conference Centers in the United States are located at: Michigan State University, Gallaudet University and the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (Cal Poly Pomona).

Academics

A view of the Tuskegee University campus – White Hall bell tower

The academic programs are organized into five Colleges and two Schools: : (1) The College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences; (2) The College of Arts and Sciences; (3) The Brimmer College of Business and Information Science; (4) The College of Engineering; (5) The College of Veterinary Medicine, Nursing and Allied Health; (6), The Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science; and (7) The School of Education.

Tuskegee houses an undergraduate honors program for qualified rising sophomores (and above) with at least a cumulative 3.2 GPA.[14]

Tuskegee University is accredited with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award Baccalaureate, Master's, Doctorate, and professional degrees. The following academic programs are accredited by national agencies: Architecture, Business, Education, Engineering, Clinical Laboratory Sciences, Nursing, Occupational Therapy, Social Work, and Veterinary Medicine.

Tuskegee University is the only Historically Black University to offer the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (D.V.M.); its School of Veterinary Medicine was established in 1944. The school is fully accredited by the Council on Education of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA).

College of Veterinary Medicine – Fredrick D Patterson Hall

Tuskegee University offers several Engineering degree programs all with ABET accreditation.

The Aerospace Science Engineering department was established in 1983. Tuskegee University is the first and only Historically Black University to offer an accredited B.S. degree in Aerospace Engineering. The Mechanical Engineering Department was established in 1954 and the Chemical Engineering Department began in 1977; The Department of Electrical Engineering is the largest of five departments within the College of Engineering. The program is accredited by EAC/ABET (Engineering Accreditation Commission/Accreditation Board of Engineering and Technology) and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

College of Engineering – Luther H. Foster Hall has long been home to one of the nation's best engineering programs containing: Aerospace Science Engineering, Chemical Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Materials Science Engineering, Mechanical and Military Science

The Tuskegee University Andrew F. Brimmer College of Business and Information Science is fully accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB-International).

The school of Nursing was established as the Tuskegee Institute Training School of Nurses and registered with the Alabama State board of Nursing, September 1892 under the auspices of the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital. In 1948 the university began its baccalaureate program in Nursing; becoming the first nursing program in the state of Alabama. The Nursing department holds full accreditation from the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission and is approved by the Alabama State Board of Nursing.

Tuskegee University School of Nursing – Basil O'Connor Hall. Tuskegee Institute Training School of Nurses was registered with the State Board of Nursing in Alabama in September 1892 under the auspices of Tuskegee University's John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital. In 1948, the School began its baccalaureate program leading to the Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing. This program has the distinction of being the first Baccalaureate Nursing program in the State of Alabama.

The Occupational Therapy program is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE) of the American Occupational Therapy Association. The Clinical Laboratory Science Program is accredited by the National Accrediting Agency for Clinical Laboratory Sciences. (NAACLS)

Tuskegee University began offering certificates in Architecture under the Division of Mechanical Industries in 1893. The 4-year curriculum in architecture leading to the Bachelor of Science degree was initiated in 1957 and the professional 6-year program in 1965. The Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture offers two professional programs: Architecture, and Construction Science and Management. The 5-year Bachelor of Architecture program is fully accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB). Graduates of the program are qualified to become registered architects.

Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science is home to one of only 2 NAAB-accredited, architecture professional degree programs in the state of Alabama. It is also home to one of the top Construction Science and Management degree programs in the nation.

Rankings

- Tuskegee is tied for 4th place with Morehouse College in the 2017 U.S. News and World Reports HBCU Rankings. Tuskegee is the highest ranked HBCU in Alabama.[15]

- Tuskegee is ranked the 5th "Best Regional College in the South" according to the 2013 U.S. News and World Reports Rankings[16]

Forbes magazine ranks Tuskegee #6 for "Best Colleges for Women in STEM programs" and ranks Tuskegee among the "600 best colleges and universities" in the country.[17]

- Tuskegee is ranked 2nd among baccalaureate colleges according to the Washington Monthly 2015 Rankings.

Schools and colleges

- College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Science[18]

- College of Arts and Sciences[19]

- College of Business and Information Science[20]

- College of Engineering[21]

- College of Veterinary Medicine, Nursing and Allied Health[22]

- School of Architecture and Construction Science[23]

- School of Education[24]

- School of Nursing and Allied Health[25]

National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care

National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care is the nation's first bioethics center devoted to engaging the sciences, humanities, law and religious faiths in the exploration of the core moral issues which underlie research and medical treatment of African Americans and other under-served people. The official launching of the Center took place two years after President Bill Clinton's apology to the nation, the survivors of the Syphilis Study, Tuskegee University, and Tuskegee/Macon County, Alabama for the U.S. Public Health Service medical experiment (1932–1972), where 399 poor—and mostly illiterate—African American sharecroppers became part of a study on non-treating and natural history of syphilis.[26]

Athletics

Tuskegee is a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division II and competes within the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SIAC). The university has a total of 10 varsity sports teams, five men's teams called the "Golden Tigers", and five women's teams called the "Tigerettes".

Tuskegee's Men's Basketball won the 2014 SIAC Championship and the 2014 NCAA Division South Region Championship. The Golden Tigers also made it to the Elite Eight during the 2014 NCAA Men's Division II Basketball Tournament. Tuskegee's Women's Softball won the 2014 SIAC Championship.

The Tuskegee Department of Athletics sponsors the following sports:

Men's athletic teams

| Women's athletic teams

|

Football

Tuskegee University's historic Cleveland Leigh Abbott Memorial Alumni Stadium, completed 1924. The stadium was the first of its kind to be built at any HBCU in the south.

The Tuskegee University football team has won 29 SIAC championships (the most in SIAC history). As of 2013 the Golden Tigers continue to be the most successful HBCU with 652 wins.

In 2013 Tuskegee opted not to renew its contract to face rival Alabama State University (Division I FCS) in the Turkey Day Classic, the oldest black college football classic in the country. Instead, after going 10–2 the Golden Tigers made their first playoff appearance in school history for the 2013 NCAA Division II Football Championship, for which they had qualified in the past but could not participate due to the Turkey Day Classic. Tuskegee competed against the University of North Alabama in the first round of the playoffs, but lost 30–27.

Tuskegee won the 2014 SIAC Football Championship and advanced to the first round of the NCAA Division II football playoffs with a loss of 20–17 to University of West Georgia.

Tuskegee lead the nation in 2013 Division II football average attendance for their three home games.[27]

Baseball

The baseball program has won thirteen SIAC championships and has produced several professional players, including big-leaguers Leon Wagner, Ken Howell, Alan Mills and Roy Lee Jackson.

Softball

Tuskegee defeated Albany State University, 11–7, to claim the 2014 SIAC Softball Championship.

Basketball

Tuskegee won the 2013–14 SIAC Championship and advanced to the 2014 NCAA Division II Men's Basketball Tournament. Tuskegee won the NCAA Division II South Regional Championship by defeating Delta State University 80-59.

The Golden Tigers fell to No. 1-ranked Metro State (Metropolitan State University of Denver), 106-87, in the Elite Eight of the NCAA Division II tournament at Ford Center, in Evansville, Indiana.

Track and field

Track began (Men and Women) at Tuskegee in 1916. The first Tuskegee Relays and Meet was held on May 7, 1927; it was the oldest African American relay meet.

The Tuskegee women's team won the championship of the Amateur Athletic Union national senior outdoor meet for all athletes 14 times in 1937–1942 and 1944–1951. The team likewise won the AAU national indoor championship four times in 1941, 1945, 1946 and 1948.[28]

Tuskegee's Alice Coachman was the first African American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in any sport, at the 1948 Olympic Games in London. Iram Lewis, a Tuskegee graduate of architecture, is an Olympian relay runner who competed for the Bahamas.

Student organizations

- SGA

- Golden Voices Concert Choir

- Marching Crimson Piper Band

Tuskegee University's marching band is the oldest of all HBCU marching bands, beginning in 1894.

- Cheerleaders

- Golden Essence Dance Team

- Miss Tuskegee University

- Mr. Tuskegee University

- Greek Life

National Pan-Hellenic Council

- Alpha Phi Alpha

- Alpha Kappa Alpha

- Kappa Alpha Psi

- Omega Psi Phi

- Phi Kappa Psi

- Delta Sigma Theta

- Phi Beta Sigma

- Zeta Phi Beta

- Sigma Gamma Rho

- Iota Phi Theta

- T.U. Greek C.O.N.S.O. Organizations

- International Students Association (ISA)

National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE)

Society of Women Engineers (SWE)- American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS)

- National Organization of Minority Architecture Students (NOMAS)

- The Newman Club of Tuskegee

- Tuskegee University NAACP College Chapter

- Alpha Phi Omega

- Gamma Sigma Sigma

- Kappa Kappa Psi

- Tau Beta Sigma

- Pershing Rifles

- Pershing Angels

- Gamma Pi Alpha service sorority

- Delta Phi Delta dance fraternity

Notable faculty and staff

| Name | Department | Notability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

J. Pius Barbour | (1919–1921) | Executive director of the National Baptist Association, editor of the National Baptist Voice, mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. | [29] |

George Washington Carver | African American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor whose studies and teaching revolutionized agriculture in the Southern United States | ||

C. M. Battey | Photography (1916–1927) | photographer who made portraits of many black leaders and shot covers for The Crisis magazine | |

George Washington Carver | African American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor whose studies and teaching revolutionized agriculture in the Southern United States | ||

General Daniel "Chappie" James | fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force, who in 1975 became the first African American to reach the rank of four-star General | ||

P. H. Polk | Photography (1933–1938) | photographer who documented working class African Americans, ex-slaves, and black leaders; also served as the institute's official photographer for four decades. | |

Ruth Logan Roberts | Physical education | Suffragist, YWCA leader on national level, activist for social and women's health issues, and host of a salon in Harlem | [30] |

Lamina Sankoh | early Sierra Leonean nationalist politician who taught at Tuskegee in the late 1920s | ||

Robert Robinson Taylor | first African American graduate of MIT, architect for most of the Tuskegee campus buildings and founder of trades programs, served as second in command to Tuskegee's founder and first president, Dr. Booker T. Washington | ||

Andrew P. Torrence | President of Tennessee State University (1968-1974); executive vice president and provost of Tuskegee University (1974-1980) | [31] | |

Booker T. Washington | Appointed President for 1881–1915 | first principal of the university | [32] |

Josephine Turpin Washington | Mathematics | 1886 Howard University alumni, early writer on civil rights topics | [33] |

Nathaniel Oglesby Calloway | Chemistry | 1930 Iowa State University alumni, first African-American to receive PhD |

Notable alumni

This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability or notability policies. (January 2018) |

US Air Force general Daniel "Chappie" James Jr.

Writer and poet Claude McKay

Singer and musician Lionel Richie

Aviator John Robinson

Actress Danielle Spencer

| Name | Class year | Notability | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

Chalmers Archer | 1972 | author of "Growing Up Black in Mississippi" and "Green Berets in the Vanguard" | |

Robert Beck | 1970s writer known as Iceberg Slim | ||

Amelia Boynton Robinson | 1927 | international civil and human rights activist, the first woman from Alabama to run United States Congress in 1964 (affectionately known as "Queen Mother Amelia"), best known for her role in the "Bloody Sunday" event in Selma, Alabama on March 7, 1965 | |

Roscoe Simmons | 1899 | columnist for the Chicago Tribune | |

William A. Campbell | 1937 | a member of the Tuskegee Airmen who rose to the rank of Colonel | |

Charles William Carpenter | 1909 | Baptist minister and civil rights activist | |

Carl Henry Clerk | 1925 | Gold Coast educator, administrator, journalist, editor, Presbyterian minister and fourth Synod Clerk, Presbyterian Church of the Gold Coast | |

Alice Marie Coachman | 1942 | athlete who specialized in high jump, and was the first black woman to win an Olympic gold medal | |

The Commodores | 70s R&B band whose members met while attending Tuskegee | ||

George Williamson Crawford | lawyer and city official in New Haven, Connecticut | [34] | |

Leon Crenshaw | former NFL player | ||

| General Oliver W. Dillard | retired Army major general, Silver Star recipient in Korea – 1950 | ||

Ralph Ellison | scholar, author of Invisible Man | ||

Milton C. Davis | 1971 | lawyer who researched and advocated for the pardon of Clarence Norris, the last surviving Scottsboro Boy | |

Cecile Hoover Edwards | B.A. 1946, M.A. 1947 | Nutritional researcher and government consultant | [35] |

Vera King Farris | 1959 | President of Richard Stockton College of New Jersey from 1983–2003 | [36] |

Isaac Fisher | educator, taught at Hampton University and Fisk University | ||

Drayton Florence | NFL defensive back | ||

Lovett Fort-Whiteman | political activist and Comintern functionary | [37] | |

Manet Harrison Fowler | 1913 | singer, founder of Mwalimu School in Harlem, president of Texas Association of Negro Musicians | |

Alexander N. Green | U.S. Representative from Texas's 9th congressional district | ||

Alexander N. Green | U.S. Representative from Texas's 9th congressional district | ||

Winston C. Hackett | First African-American physician in Arizona | [38][39] | |

Marvalene Hughes | president of Dillard University | ||

General Daniel "Chappie" James | 1942 | US Air Force Fighter pilot, in 1975 became the first African American to reach the rank of four-star General | |

Lonnie Johnson (inventor) | inventor of the Super Soaker, former NASA aerospace engineer | ||

Ken Jordan | former NFL player | ||

Tom Joyner | 1971 | radio host whose daily program, The Tom Joyner Morning Show, is syndicated across the United States and heard by over 10 million radio listeners. | |

John A. Lankford | 20th century architect | ||

Marion Mann | 1940 | former dean of the College of Medicine at Howard University and US Army Brigadier General (retired) | |

Claude McKay | 1912 | Jamaican writer and poet, Harlem Renaissance | |

Albert Murray | 1939 | literary and jazz critic, novelist, and biographer | |

Ray Nagin | 1978 | former mayor of New Orleans, Louisiana | |

Dimitri Patterson | NFL player | ||

Dr. Ptolemy A. Reid | 1955 | Prime Minister of Guyana (1980–1984) | |

Rich Boy | Rapper | ||

Lionel Richie | R&B singer, Grammy Award winner | ||

Lawrence E. Roberts | a member of the Tuskegee Airmen and a colonel in The United States Air Force | ||

John Robinson (aviator) | early aviator and colonel in the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force against Fascist Italy during WWII | ||

George C. Royal | 1943 | microbiologist who is currently professor emeritus at Howard University | |

Roderick Royal | president of the Birmingham City Council | ||

Betty Shabazz | wife of Malcolm X | ||

Jake Simmons Jr. | 1919 | oil broker and civil rights advocate | |

Danielle Spencer | television actress best known as Dee from the 1970s TV show What's Happening!! | ||

McCants Stewart | 1896 | lawyer, first African American to practice law in Oregon | |

Frank Walker | NFL defensive back | ||

Keenen Ivory Wayans | actor, comedian, and television producer | ||

Alfreda Johnson Webb | 1943 | First African-American woman in the North Carolina General Assembly (1972) | [40] |

Jack Whitten | abstract painter | ||

Dr. David Wilson | president of Morgan State University | ||

Roosevelt Williams (gridiron football) | 2000 | former NFL player for the Chicago Bears, Cleveland Browns, New York Jets | |

Ken Woodard | former NFL player | ||

Elizabeth Evelyn Wright | educator and humanitarian, founder of Voorhees College | ||

Marilyn Mosby | 2002 | State's Attorney in Baltimore, MD |

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Alabama

References

^ NAICU – Member Directory Archived 2015-11-09 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-27. Retrieved 2018-05-26.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Visual identity and COmmunications Policies for Tuskegee University (PDF). 2012-08-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-05. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

^ Thomas, Grace Powers (1898). Where to educate, 1898–1899. A guide to the best private schools, higher institutions of learning, etc., in the United States. Boston: Brown and Company. p. 5. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

^ Washington, Booker (1995). Up From Slavery. Dover. p. 127.

^ "Olivia Davidson Washington." Notable Black American Women. Gale, 1992. Biography In Context. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

^ Guridy, Frank. Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

^ Dominguez, Alex (2006-05-06). "Booker T. Washington's Death Revisited". Washington Post. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

^ Andrew E. Barnes, Global Christianity and the Black Atlantic: Tuskegee, Colonialism, and the Shaping of African Industrial Education (Baylor University Press, 2017).

^ "The Tuskegee Airmen and Eleanor Roosevelt". Archived from the original on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

^ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

^ ab "Tuskegee Institute". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

^ ab Horace J. Sheely, Jr. (1965-03-01) National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings: Tuskegee Institute, National Park Service and Accompanying 20 or so photos, undated.

^ "Honors Program – Tuskegee University". Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

^ http://hbculifestyle.com/hbcu-rankings-2017-top-25/

^ "Best Regional Colleges USNWR". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

^ Doss, Natalie (2010-12-15). "Best Colleges for Women and Minorities in STEM". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

^ "CAENS | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "CLAE | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "CBIS | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "CEAPS | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "CVMNAH | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-02-19. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-02-27. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "School of Education | Tuskegee University". Tuskegee.edu. 2011-07-01. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

^ "SONAH | Tuskegee University". www.tuskegee.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

^ "Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care". Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

^ "2013 NATIONAL COLLEGE FOOTBALL ATTENDANCE" (PDF). Retrieved 11 May 2015.

^ Tricard, Louise Mead (1996). American Women's Track and Field – A History, 1895 through 1980. Jefferson, North Carolina, U.S.: McFarland & Co., Inc.

^ "Barbour, Joseph Pius". www.kinginstitute.stanford.edu. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

^ Alexander, Adele Logan. "Roberts, Ruth Logan". Religion and Community. Facts On File, 1997. African-American History Online. Retrieved 6 February 2016. Sourced from Hine, Darlene Clark; Thompson, Kathleen, eds. (1997). Facts on File encyclopedia of Black women in America. New York, NY: Facts on File. ISBN 9780816034246. OCLC 906768602.

^ "Dr. Andrew Torrence, 3rd TSU President, Dies". The Tennessean. June 12, 1980. pp. 6, 18 – via Newspapers.com. (Registration required (help)).

^ "Tuskegee University". tuskegee.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-08-20.

^ Penn. The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, 1891, pp.393–396 Retrieved December 4, 2013

^ "George W. Crawford Black Bar Association". Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Warren, Wini (1999). Black Women Scientists in the United States. Indiana University Press. pp. 88–92. ISBN 0253336031.

^ "Vera King Farris, Stockton college's longest-serving president, dies after short illness – pressofAtlanticCity.com: Education". pressofAtlanticCity.com. 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

^ Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia. New York: Penguin Press, 2008; pg. 98.

^ "Airzona Informant". Archived from the original on 2017-09-25. Retrieved 2017-12-30.

^ Color Blind Care

^ Hairston, Otis L. Greensboro North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Further reading

Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919, 320-327. University of Illinois Press, 2004. Early recordings by the Tuskegee Institute Singers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tuskegee University. |

- Official website

- Tuskegee Athletics website

- Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site at Google Cultural Institute